- Home

- Companies

- Isle Utilities

- Articles

- The Trial Reservoirs Initiative Four ...

The Trial Reservoirs Initiative Four Years On

A Milestone for Turning Water Innovation Into Adoption

The problem we set out to solve

Four years ago, in the aftermath of yet another global climate summit heavy on ambition but depressingly light on delivery, the Trial Reservoirs Initiative was conceived to challenge the water sector’s most persistent failure: the gap between proving a technology works and actually using it. We knew lack of innovation wasn’t the problem; the sector was rich in proven but unfamiliar solutions. What was missing was a reliable mechanism to move from “this worked” to “this is now how we operate”.

Technologies are routinely demonstrated successfully only to stall when commitment is required. Utilities invest time in trials, generate credible results, and then return to business as usual. Measured by adoption rather than experimentation, the sector’s track record has been stubbornly poor. This is a failure of process rather than a failure of engineering or ambition. Consequently, our goal was not to run better pilots, but how to design trials that make inaction the harder choice.

That challenge shaped everything that followed. The Trial Reservoirs Initiative was created to reverse the status quo, and to accept failure where technologies do not deliver, but require action where they do. In late 2021, this moved from theory into practice with the launch of the Climate Change Trial Reservoir – a model built explicitly to shorten the distance between testing something new and making it business as usual.

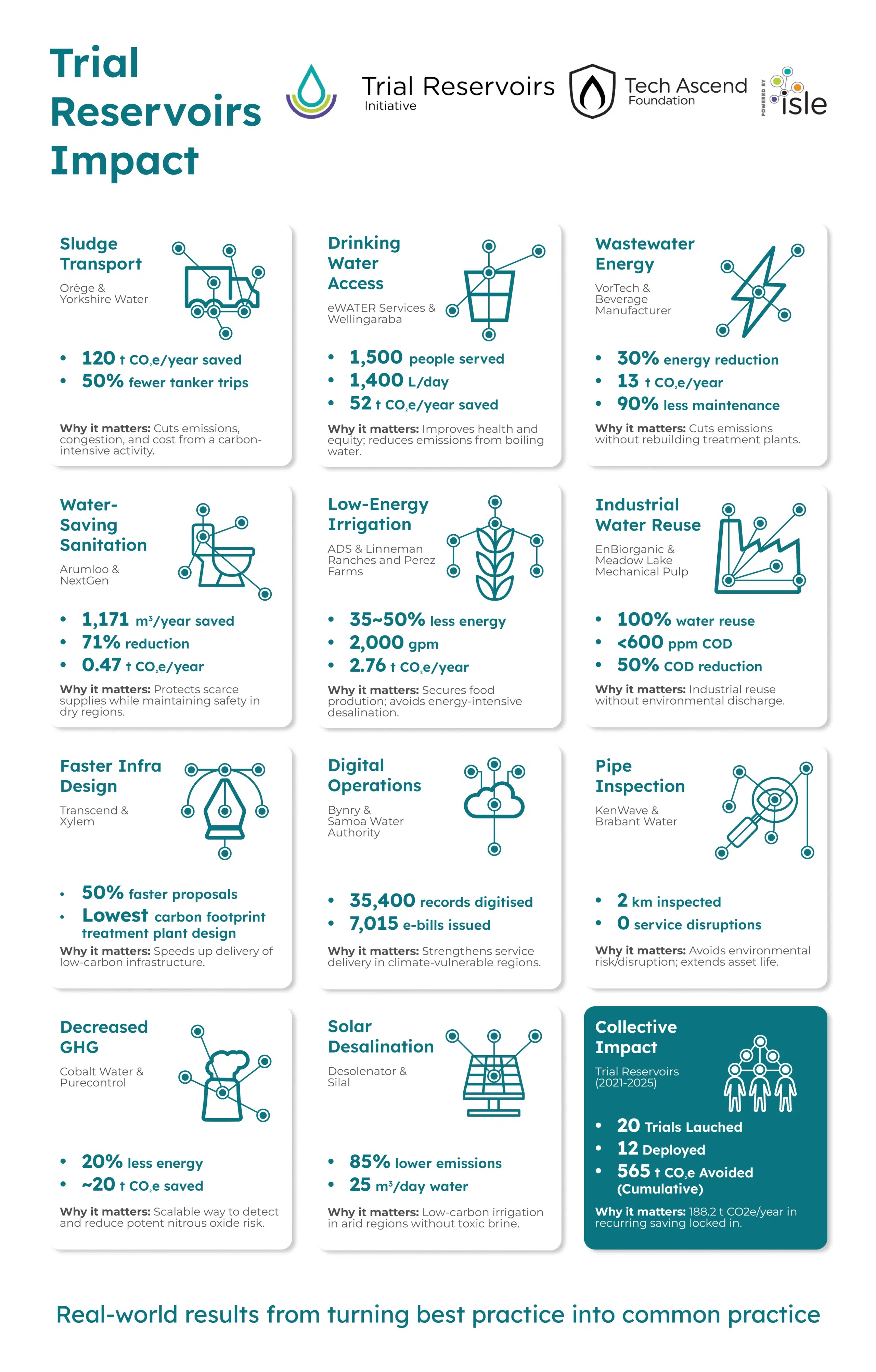

Four years on, the Initiative has launched 20 globally, with 17 completed to date. Of those, 12 (70%) concluded successfully. More importantly, that performance has translated into adoption, with 12 technologies now commercially deployed in real systems.

For those interested in the numbers, the Initiative has helped deliver 188.2 tonnes of CO2e savings per year across five trials with quantified carbon impacts, and has avoided around 565 tonnes of CO2e cumulatively since 2021. Crucially, these savings are locked in through adoption, continuing long after the trials end.

While we’re immensely proud of the individual trials, their real value lies in shifting normal practice. Our largest carbon savings consistently come from a few levers: using less energy to deliver the same outcome, reducing transport, and cutting water use where it equates to energy demand.

The operating model is designed for scale. Through framework contracts, a single successful trial can unlock rollout across multiple comparable assets,. Based on our current pipeline of more than 450 technologies, there is a credible pathway to around 65,000 tonnes of CO2e saved per year, with the potential to exceed 100,000 tonnes annually as adoption spreads.

To put that in context, 65,000 tonnes of CO2e per year is roughly equivalent to burning 25 million litres of diesel. In the water sector, these savings are small, cumulative changes: fewer sludge tankers on the road, treatment works drawing slightly less power hour after hour, pumps running less often, and processes optimised once and then left to do their job. Scaled across assets, regions, and organisations, these incremental gains quietly become the new normal.

The Initiative succeeds because it is built for difference. The water cycle involves complex physical, chemical, and biological processes that rarely behave in predictable ways. Instead of trying to smooth out that complexity, our model works with it, holding steady across very different parts of the system.

That range of contexts doesn’t mean starting from scratch each time. What matters is getting the trial right, and this the magic of our Trial & Purchase Agreement (T&PA). The T&PA is flexible regarding trial execution but rigid on objective performance measures. Trials are designed to be scientifically robust and proportionate, and to run only for as long as it takes to reach a decision. We don’t default to a six-month trial. In some cases, six months isn’t nearly enough; in others, clear conclusions can be reached in a matter of weeks. Trial design, key performance indicators, monitoring, and post-trial commitments are shaped around the technology and its setting, rather than squeezed into a ‘one size fits all’ template.

The philosophy is simple: try it, determine objectively whether it worked, and if it did, use it. While implementation is rarely simple, the principles apply across the system.

The model has evolved as we’ve learned what works and what doesn’t. When trials haven’t progressed as hoped, we’ve adjusted the model to address the underlying reasons. We’ve had five trials that did not proceed to implementation and while that was disappointing, each one made the Initiative stronger. In most cases, the technology itself wasn’t the problem; it was the context around it that proved harder than expected.

Two lessons stand out. First, change inside water organisations rarely follows a straight line. Running a trial is often achievable; embedding something new into day-to-day operations is much harder. It takes time, ownership, and sustained attention. This is where the Trial & Purchase Agreement has been crucial, setting expectations and commitments upfront instead of relying on goodwill once a trial ends.

Second, a technology can work well and still struggle with real world constraints, such as supply chains, or bespoke components. Likewise, if baselines or operating conditions aren’t properly understood, even robust technologies can falter. We now test assumptions early, rather than uncovering constraints when it’s too late to change course.

To this point, we have learned that time spent on setup is rarely wasted. A rushed trial with no credible path to adoption is far less useful than deciding not to proceed at all. A recent trial in Brazil illustrates this clearly. The setup phase took nearly two years; the trial itself ran for just eight weeks. This balance was intentional. Rather than rushing into testing, the teams focused on understanding the site, validating assumptions, and being clear about what success would look like. While a utility could initiate a trial much faster without a T&PA, the picture can become murky when the trial ends, even if it goes well. Real world constraints then surface and utilities often spend years working out whether and how to implement – by which point the original rationale and momentum may well have evaporated. While a two year setup phase may ‘feel’ long, the result is a trial that will progress seamlessly to implementation, rather than being shelved once the pilot has concluded.

The model is now more realistic, more resilient, and designed to work within the realities utilities face.

There is no escaping the fact that changing operational systems is difficult. Assets are long-lived, risks are real, and capacity is constrained. That difficulty is precisely why the sector has become adept at piloting without adopting. However, we have seen that when trials are established with clear objectives, and an agreed route to implementation, organisations follow through. Not because it is easy, but because the structure makes commitment unavoidable once uncertainty has been removed.

The diversity of technologies progressed through the Trial Reservoirs Initiative reiterates that the barrier has never been the science. It has been the way we as a sector trial, decide, and commit. This milestone demonstrates that a different approach is not only possible, but repeatable, and that it’s possible for adoption to become part of normal practice.

Things have changed for us too. By 2025, it was clear that while the model was working, it needed to scale faster to match the urgency of the climate and water challenges ahead. Twelve new technologies working their magic out in the wild is a feat, but it’s not enough. That led to the Trial Reservoirs Initiative evolving into an independent not-for-profit as part of the Tech Ascend Foundation. This change is opening new avenues for philanthropic and mission-aligned funding to continue to accelerate adoption. This shift means that our individual Reservoirs can be replenished more reliably and deployed where they are most needed.

For utilities considering the Initiative, our message from the last four years is this: this is not an innovation programme designed to generate pilots for their own sake. It is a decision-making mechanism designed to generate change.

Our model works within the realities of regulatory oversight, procurement rules, operational risk, and limited room for blue sky thinking. We don’t ask organisations to take reckless bets, but we do ask them to be decisive when the evidence justifies it. In return, the Initiative supports the outcomes utilities are already under pressure to deliver: net zero carbon, improved efficiency, resilience, and better value for customers.

Ultimately, the value of the Trial Reservoirs Initiative is not that it produces successful pilots. It is that it shortens the gap between learning and action. For utilities that are serious about moving beyond trials and embedding new ways of working, the message from four years of practice is clear: adoption at pace is possible, but only when commitment is designed in from the start.